Early in 2023, when people massively used ChatGPT, the “hallucination” term became common as it was the most frustrating part of the experience: one would seldom not find an answer to a question but encounter one that was convincing but untrue. In my experience, I faced it in the form of inexisting functions or software packages: the answer was utterly fabulous, except I wouldn’t find that package to install and use.

In this post, I play with a toy case to gather evidence to identify hallucinations. The central assumption is that the truth might be said differently. Still, it doesn’t change in meaning while making up an alternative reality opens up very different information - though they might all seem plausible.

I was curious to see if we could use the same approach of bootstrapping tabular data models to verify the uncertainty on the prediction to tell about the uncertainty about the generated content. I show how variance changes with hallucination and how to pick one candidate as the final prediction.

It is not currently expected to rely on an LLM’s internal knowledge, and the Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is the current approach to let users control the knowledge base to be considered. I won’t cover this case, though.

OpenAI has been clearly improving on it, and one can see GPT-4 refrains from answering when it doesn’t know the subject. This issue will likely be solved internally on LLMs.

Edit: after publishing this post, I end up finding a work called “SelfCheckGPT” 1, which uses the same assumption that hallucination will generate different answers for the same question, but then use a different approach to verify it by using an LLM to evaluate it.

Temperature and hallucinations

The temperature argument controls the randomness and diversity in the generated text. It is used for sampling in LLMs. Because of it, the temperature=0 became a mantra for non-hallucination. However, the key to spot it is precisely on temperature>0, because it provides us variability.

Imagine you recruit ten liars for a “lie contest”. They need to convince people their wrong answer to the same question is true. Though they might convince ten different people who heard their lies individually, it becomes clear they are lying when you put the ten answers together.

Now imagine a “poetry contest”, and you ask ten poets to “describe me the sky”. They can be very creative and use different images to explain it, but when you put them together, there will be a higher semantic similarity among them than in the case of the liars.

Temperature can be an ally in identifying hallucinations instead of an enemy. When questions are open and hard to answer, or when the LLM hasn’t the resources to answer them, it is more prone to hallucinating. When it has confidence, a higher temperature won’t introduce meaning variability. At the most, they bring form variability.

Toy experiment

The data and code can be found in a gist and a collab notebook.

We will use two datasets. One is “synthetic”, and the other uses actual outputs from GPT-3.5 for two questions. They are both anecdotal, and I can expand on it if I find a good dataset.

The first is generated using ChatGPT 3.5 with the following prompt:

I want you to create two python lists. One contains 10 hallucinating (hallucination as seen in large language models) answers, and the other contains the same valid answer but written differently for the question “Question: Can you explain the steps a customer should follow when seeking support from their bank regarding a potential fraudulent transaction on their account?”. The answers in both hallucinating and valid groups should have similar lengths. They should be similar to the customer service tone of a bank.

And here are the three examples of hallucinating and valid answers to the question:

Hallucination:

- “Sure, the first thing you need to do is gather all the data related to the stock market because stock fluctuations may impact the fraudulent transaction. Then write a poem about your feelings regarding this fraudulent transaction, which helps keep your emotions in check. Following this, you may consider contacting the person who committed the fraud, they might change their mind and return the money.”

- “It’s important to contact authorities about possible extraterrestrials that may be involved in the fraudulent activity. Analyze the patterns of the planets, sometimes they align in such a way that increases the chances of fraudulent activity.”

- “Before contacting your bank, make sure to solve three crossword puzzles. This sharpens your mind and helps you communicate your concerns more effectively. If the fraudulent transaction was done on a Tuesday, wear a blue shirt while reporting it.”

Valid:

- “Certainly, the first thing you should do is to identify and confirm the suspicious transaction on your account. Then, contact your bank immediately through their dedicated helpline for fraudulent transactions. The bank would guide you through necessary measures to secure your account.”

- “Sure, start by noting down the details of the fraudulent transaction and then call your bank’s customer service line. You’ll be guided on how to report and refute the transaction, and they will also provide instructions to prevent further fraud.”

- “Of course, first ensure you have all details of the fraudulent transaction readily available. Subsequently, get in touch with your bank’s customer support to inform them about the incident and seek assistance on the next steps.”

Variability and hallucinations

To spot variability, I will transform the different answers I get for the same question in an embedding, which will make it possible to compare their semantic meaning. If two answers have the same sense, they will have a high similarity, even if they are relatively different.

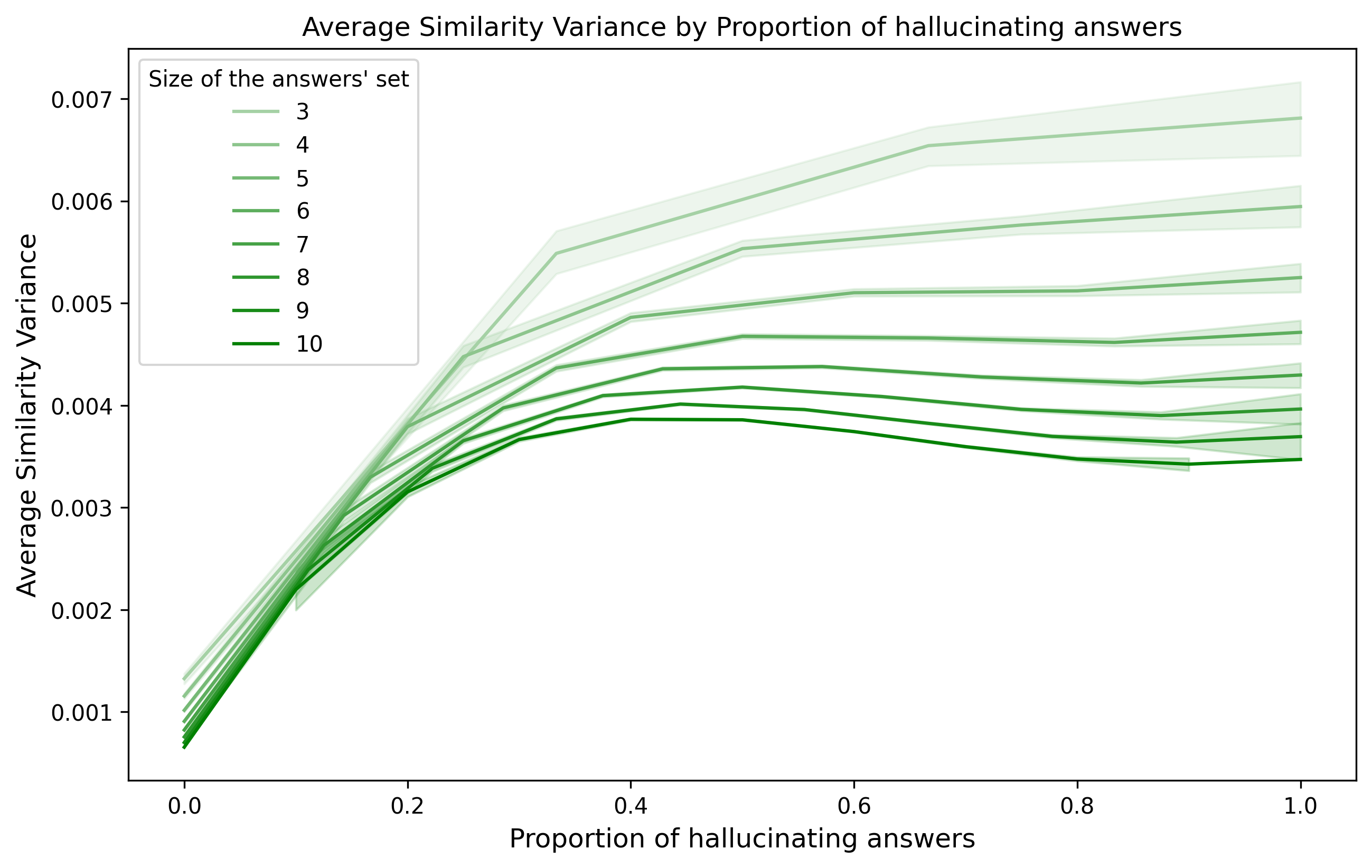

Then, I create different sets of answers for the same question, varying the set size from 3 to 10 and mixing valid and hallucinating answers.

For every different set, I calculate the similarity score for every pair of answers inside it. Then, I calculate the variance of all the similarity scores.

It means that for every set of answers, I have its size, the proportion of hallucinating answers, and the variance of the pair-wise similarity score.

I plot it by showing how the similarity variance changes as I insert more hallucinating answers in the set. In contrast, I show different curves to display the effect of the set size.

We can see the similarity will vary more when hallucination is happening. We can use it as evidence hallucination is occurring for a given question and choose not to answer it. It tells us we are in the case of the “lie contest” and not the “poetry contest”.

Splitting good answers from the noise

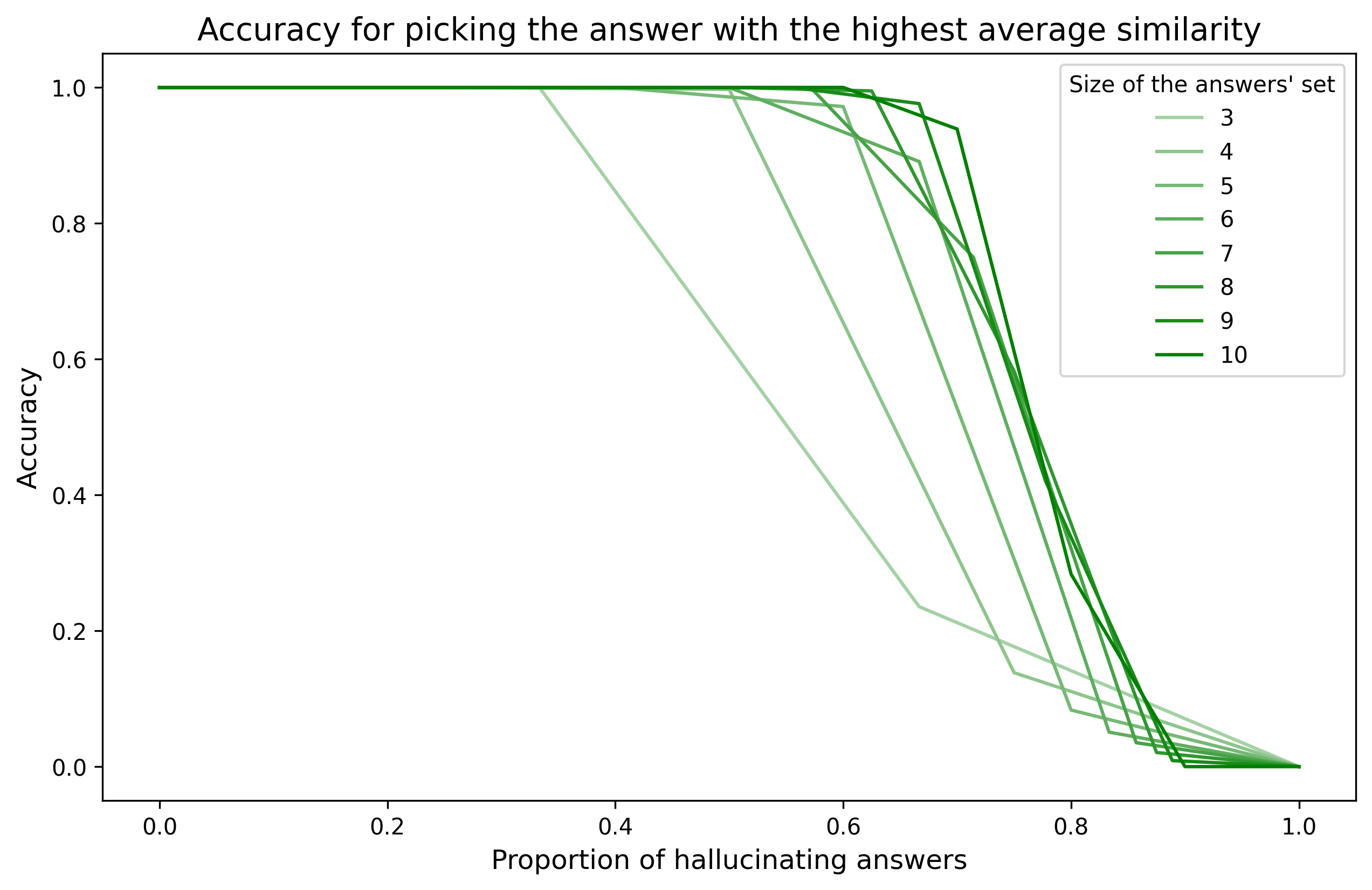

I’m unsure how often LLMs will produce sets with hallucination proportions higher than zero and lower than one to generate a second task of picking the best answer using logic instead of randomly. However, let’s assume we will have this risk, and we need to pick a non-hallucinating answer. In this case, we can look at the pair-wise and variance average by the answer, choosing the one with the most similarity with the other options.

The intuition is that it is unlikely the hallucinations will be similar to each other, while the non-hallucination answers will only be similar to hallucinating answers by chance.

Suppose we run this rule on our toy example and measure its accuracy, such as how many times this rule could pick the non-hallucinating answer in the set. In that case, we see it works pretty well, and it keeps an accuracy of 100% in the low hallucination region. The larger the set of questions, the better this rule will work on selecting a valid answer, even if there is a high proportion of hallucinating answers (50-70%).

Testing it on GPT-3.5

The second dataset was generated using GPT-3.5 to answer the questions: “What Luis Moneda is known for?” and “What Marcel Proust is known for?”. I did them in Portuguese and translated them because GPT in English has better behavior about hallucinations. I used a temperature of 1.2, max tokens of 600, and generated 10 choices.

Looking into the examples of each, we see it hallucinates about me:

- Luis Moneda is mainly known for his work as a musician, producer and DJ. He is recognized in the electronic music and hip hop scene, with several collaborations with renowned artists. Some of his most popular songs include “Sabor a Miel” and “No Me Compares.” Furthermore, Luis Moneda is also considered a social activist, supporting causes such as gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights.

- Luis Moneda is known for being a renowned economist and professor emeritus of economics at the University of Chicago. He is famous for his contributions in the areas of macroeconomics, monetary policy and financial theory. Additionally, he was Chairman of the United States Federal Reserve from 2010 to 2014 during a crucial period following the 2008 global financial crisis. Luis Moneda has also written several popular articles and books on economics and finance.

And it gets it right about Marcel Proust, regardless of the high temperature:

- Marcel Proust is known for being one of the most important French writers of the 20th century. He became especially famous for his work entitled “In Search of Lost Time”, also called “À la recherche du temps perdu”. It is a series of seven books that portrays the protagonist’s life and reflections in detail, covering themes such as memory, time, love, art and society. Proust is considered one of the great masters of modern literature and his work is admired for its philosophical depth and the richness of his prose.

- Marcel Proust is mainly known for being a renowned French writer of the 20th century, famous for his masterpiece entitled “In Search of Lost Time” (“À la recherche du temps perdu” in French). This is one of the greatest literary works ever written, where Proust explores themes such as memory, love and identity. Proust’s writing is marked by its psychological depth, poetic style, and meticulous immersion in the flow of thoughts and sensations of his characters. He is considered one of the great names in modern literature.

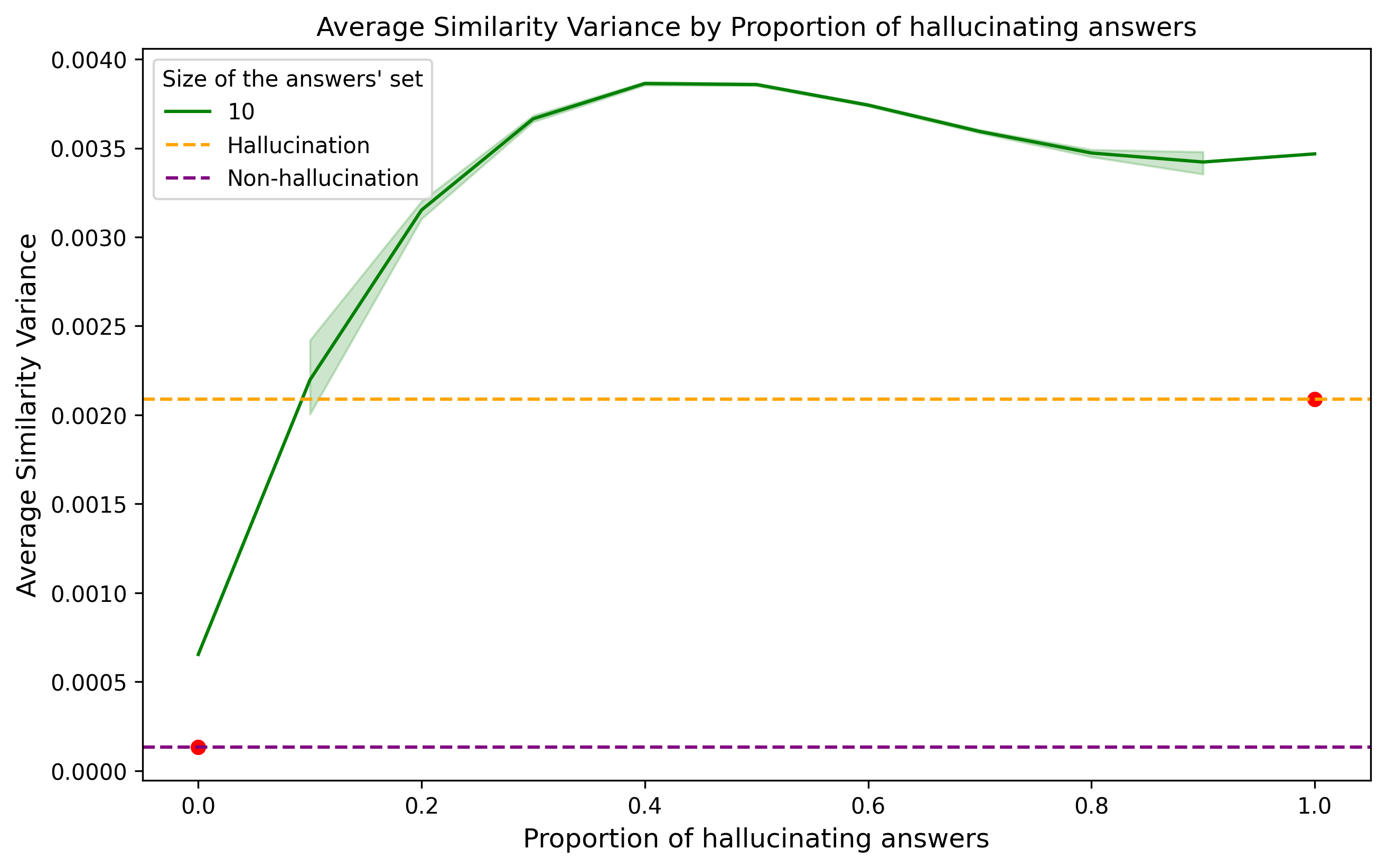

We will now check the similarity variability inside these two sets of answers and compare it to a curve we did with the previous dataset.

The question about myself is the dashed line assigned to “hallucination,” and the one about Marcel Proust is the “non-hallucination”. The non-hallucination case had an even lower variance than the fabricated data. In comparison, the hallucination case had a way lower variance but was still higher than the non-hallucination case. It is hard to make conclusions from such a toy example, but we can fit a curve for a specific domain and find a suitable region where we can trust LLMs’ answers.

Notice that an answer that says “I don’t know” in different ways will also have a low variance on the similarity score.

With a proper dataset with Q&A labeled with a hallucination tag, one can generate further answers using higher temperatures, apply a filter on variance, pick the best answer, and then perform manual labeling to verify if we would have spotted the hallucination cases or even have selected valid answers.

References

-

- Manakul, P., Liusie, A., & Gales, M. J. F. (2023). Selfcheckgpt: zero-resource black-box hallucination detection for generative large language models.